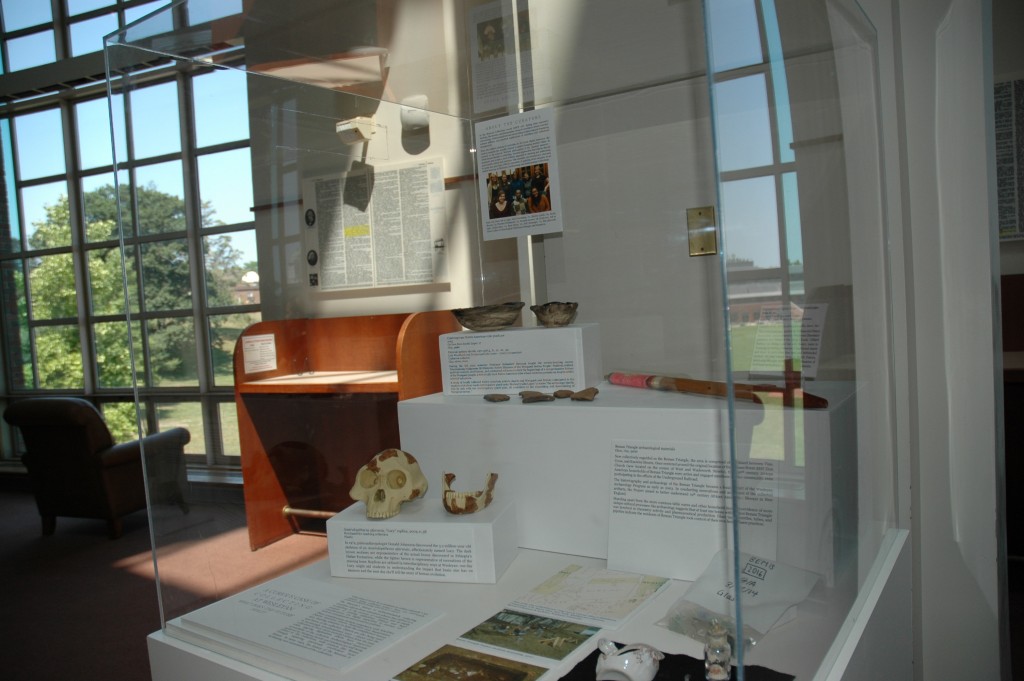

This first post was supposed to be titled ‘Around the World in 10 Objects,’ but we couldn’t decide on which object to leave off the list! An extra object, then, for good luck! All objects in this post are part of the Wesleyan University Archaeology and Anthropology Collections.

Coin, Object ID 2003.1.234, Dahl Coin Collection

Coin, Object ID 2003.1.234, Dahl Coin Collection

Place of origin: London, England

The Dahl Coin Collection consists of 262 coins mostly of Greek and Roman origin along with a few miscellaneous items. Winthrop Dahl (Wesleyan Class ’84) started his coin collection when he was in high school and continued collecting up until close to his death. Dahl was a Classical Studies major when he was a student as Wesleyan, and looked back so fondly on his years here that in his will he left his coin collection to the University. His mother, in his memory, also donated several Greek vases and terra cotta items. After graduating from Wesleyan, Dahl became a Latin teacher at a high school in Massachusetts and built up a thriving Latin program.

The Cnut coin (pronounced and sometimes written as Canute) is an AR penny from a London mint and was made by a moneyer named Edgar between ca. 1016 – 1035 CE. Cnut the Great was king of Denmark, England, and Norway during the early 11th century until his death in 1035 AD.

Gourd bowl, Object ID 1870.273.1, Missionary Lyceum Collection

Gourd bowl, Object ID 1870.273.1, Missionary Lyceum Collection

Place of origin: Monrovia, Liberia

This painted gourd bowl was collected by Reverend Mr. John Seys in the 1840s. Seys was a member of the Missionary Lyceum started by then University President Rev. Dr. Willbur Fisk. The purpose of Lyceum was to

“promote a missionary zeal among its members by way of debates, addresses, collection of artifacts and literature from foreign missions, and the exchange of correspondence with various missionaries.”

Information was gathered through correspondence with missionaries who were stationed in different places around the world. In 1840 Seys sent some collected material back to Wesleyan, including

“…a box of shells, &c, which I beg the gentlemen of the Lyceum to accept of, and to place, if they consider them of sufficient value, among the other curiosities of their cabinet.”

The Lyceum is of significant importance to the Wesleyan University Archaeology and Anthropology Collections as Lyceum missionaries became the original collectors and contributors to the artifact collection. Missionaries were asked to collect artifacts and send correspondence regarding said artifacts back to Middletown in an effort to begin a “museum.” Missionary and University  President, Rev. Dr. Willbur Fisk wrote

President, Rev. Dr. Willbur Fisk wrote

“This society will aid the [missionary cause] . . . by . . . its Missionary Cabinet or Museum. In this you have already a good beginning; but we hope that the members of the society, both the graduates and undergraduates, will exert themselves to enlarge this museum.”

Denticulate tools, Object ID 3186 KB, Mount Carmel Collections

Place of origin: Mugharet el-Kebara, Mount Carmel, Israel

Place of origin: Mugharet el-Kebara, Mount Carmel, Israel

These denticulate, or serrated, tools were excavated from the Natufian levels at Mugharet el-Kebara (Cave of the Valley), Israel. This cave is located near the Wadi el-Mughara (Valley of the Caves). The excavations were carried out in 1930-31 by the American School of Prehistoric Research (ASPR) in conjunction with the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. The Natufian culture corresponds to the Mesolithic period and ranged from 12,500 to 9,500 BCE. They were a sedentary or semi-sedentary people – even more interesting is that this occurred before the advent of agriculture. These tools belong to the Lower Natufian level, meaning their creation and use are limited specifically to 12,500 to 10,800 BCE!

Chipped stone tools are made in one of two ways: they can be the objective piece or the detached piece. Objective pieces are those from which material is removed in order to create a tool. Detached pieces are those which are taken off of an objective piece. Chipping of stone is also done in one of two ways: percussion flaking is the practice of hitting the objective piece with a hammerstone (usually made from stone but also can also be antler, bone or wood). Pressure flaking is a slightly more accurate technique consisting of applying pressure with a sharpened point, normally antler or bone. Retouching is done after this in order to create the serrated edge that is visible on the objects.

Looking glass, Object ID 907

Place of origin: Bareilly, India

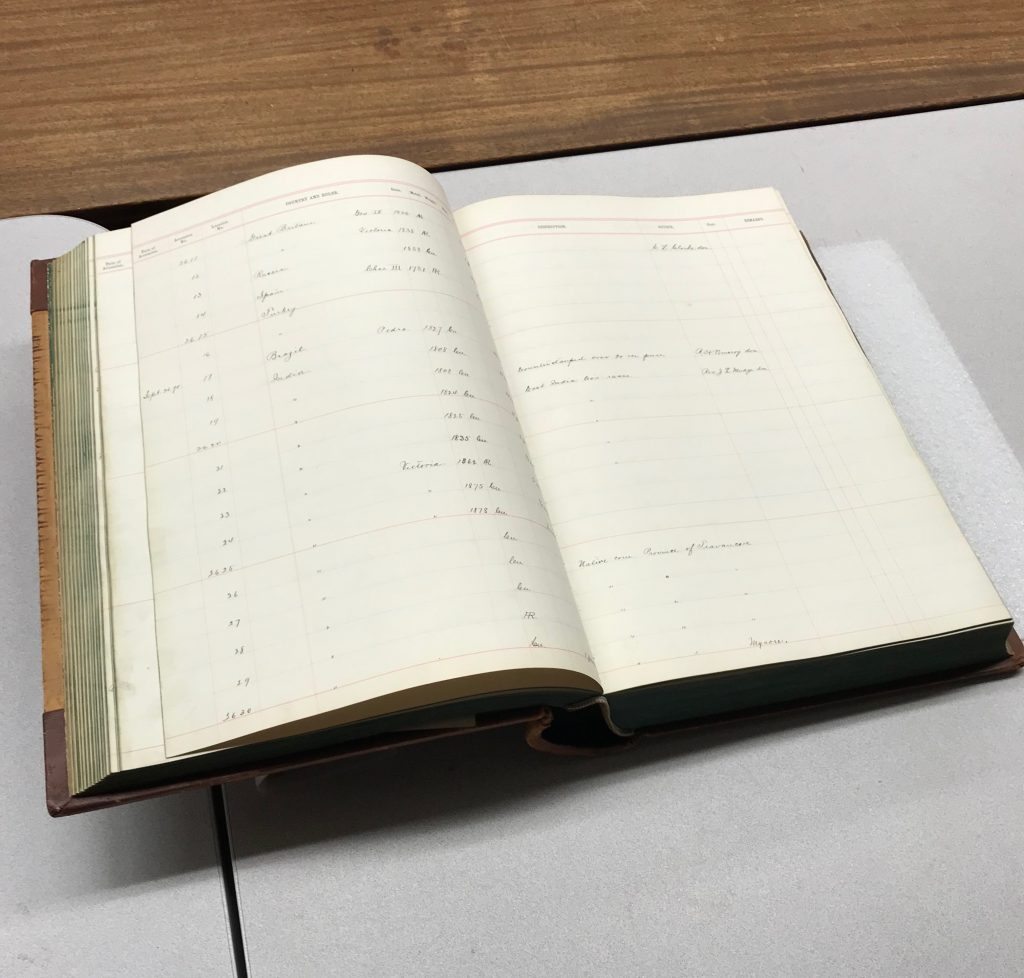

This looking glass was collected by M.L. Bannerjea and donated to Wesleyan University in 1881. The looking glass was recovered recently when another department was cleaning out their storage space in Exley Science Center. A box of artifacts, mostly collected by missionaries stationed in various parts of Asia, was found and returned to the Collections. Some of the artifacts are listed in the old museum inventories (read more about the Wesleyan Museum, 1871-1957), but others may have been in storage since the 1970s.

Tea block, Object ID 2355

Tea block, Object ID 2355

Place of origin: Foochow, China

Too bad your screen isn’t scratch and sniff right now, because this brick of tea smells amazing! Dr. John Gowdy donated three tea blocks to Wesleyan in 1914. As with the looking glass, these bricks were found recently in another department’s storage space. The tea blocks are engraved with Russian lettering – something that may at first seem surprising. With the generous help of Irina Aleshkovsky, Adjunct Professor of Russian, Eastern European Studies, we had a tea block translated. It reads,

“Pu Chzhou and Company in Hankou China

Recommended to the revered public tea under this label of a superb quality of the first crop gathering from the best plantations”

Interesting grammatical choices aside, this translation illuminates the origin and usage of the tea. Tea made in this manner was cheaper because it was from poorer quality leaves mixed with herbs and ox blood. The tea was then sold to Russian peasants because it was more affordable than regular tea leaves. Believe it or not, tea also served as a form of currency. Stuart Mosher, former Curator of Numismatics at the Smithsonian explains,

“In Siberia, Mongolia, Tibet and Chinese-Asian marts, cakes of compressed tea resembling mud-bricks circulate as money. This “money” which is manufactured in Southern China, is made of leaves and stalks of the tea plant, aromatic herbs and ox blood. It is sometimes bound together with yak dung.

“Tea is compressed into bricks of various sizes and stamped with a value that varies depending upon the quality of the tea. It usually increases as the bricks circulate farther from the tea producing country. The natives of Siberia prefer tea-money to metallic coins because of lung diseases prevalent in their severe climate, and they regard brick tea not only as a refreshing beverage but also as a medicine against coughs and colds.“

We love these tea bricks for a variety of reasons. They are so different than many of the other objects we have in the collections. Additionally, their mere existence has the ability to express a variety of cultural practices. They also demonstrate the intersections of many cultures during the early 20th century.

Fishing line with pearl shell sinker, Object ID 1874.570.1, Oceanic Collections

Place of origin: Fiji

The fishing line was collected by Captain Charles Wilkes on the US Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842. This expedition was initially requested by President John Quincy Adams, and then finally funded by the government at the request of President Andrew Jackson. Wilkes set off in 1838 with 6 ships and 346 men. One of the targeted areas of the expedition was the South Pacific. In general the purpose of the US Exploring Expedition was to develop the field of science, particularly oceanography, in the United States.

Captain Wilkes was not a well-liked man but “there was something quintessentially American about Wilkes and the brash, boisterous, and overreaching expedition that he managed to forge in his own makeshift image” (Phillbrick 2004). Wilkes’ Expedition often saw armed conflict between indigenous Pacific Islanders.

Many of the natural history specimens and ethnographic objects collected during the Wilkes Expedition became the basis for later Smithsonian Institution collections. This particular object – the fishing line with netsinker – came to Wesleyan by way of the Smithsonian in 1874. Often time collectors and museums exchanged artifacts and whole collections amongst each other. For instance, we know from the Wesleyan Museum records, that the Smithsonian traded with Wesleyan some Native American pottery for mineral and beetle collections!

Ivory knife, Object ID 1890.1031.1, Pacific Northwest/B.C./Alaska Collections

Ivory knife, Object ID 1890.1031.1, Pacific Northwest/B.C./Alaska Collections

Place of origin: Big Lake, Alaska

Edward William Nelson obtained this ivory knife while living in Alaska for about 5 years. Nelson observed children using the knife to sketch in the snow and gave it the name “snow knife.” The name in Central Alaskan Yup’ik is yaaruin, translating to “story knife.” Children, mainly girls, in fact used these knives to “sketch pictures on the ground to accompany a story or song.”

Nelson was an explorer, naturalist, and science administrator. He began his career within different facets of the United States government in 1877 as a weather observer in the Signal Corps of the United States Army, stationed in St. Michael on the Bering Sea coast of Alaska. During the next several years he made many excursions throughout the area compiling data and artifacts and observing the customs of Alaska’s indigenous peoples. The natural history and ethnographic materials that he collected became some of the early collections of the Smithsonian. Like the fishing line from Fiji, this ivory knife came to Wesleyan by way of the Smithsonian. For more information on the Nelson’s expeditions and related collections see this information from the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Moccasins, Object ID 1911.2264.1, Neff Collection

Place of origin: Canada

Charles H. Neff donated this pair of children’s moccasins to Wesleyan upon his death. Neff was an amateur archaeologist and mostly a collector of Native American material in the Middletown, CT area. He even published volumes regarding his collections. One such volume details the many Native American materials that he collected throughout the greater Middletown region between the late 1800s and early 1900s. Many of those Native American materials – primarily pottery and stone tools – were donated to the Wesleyan University Museum and now are a part of the Archaeology and Anthropology Collections.

Neff also accrued a small ethnographic collection, including these moccasins from Canada. Little more is known about the moccasins. Unfortunately, that was simply the nature of collecting in the 19th and early 20th century: the object was more important than recording its contextual information. Much can still be learned from these objects though, including what types of materials were used.

Feathered staff, Object ID 1974.4.1

Feathered staff, Object ID 1974.4.1

Place of origin: Rio Negro or Rio Tapajos region of Brazil

This feathered staff consists of a wood handle and parrot and macaw feathers. The staff was collected by Reverend D. P. Kidder in 1839 during a Missionary Lyceum expedition. Kidder donated the staff, along with other materials collected in South America, to the Wesleyan University Museum in 1870. Little else is known about the object or its original use. Although we do not have any documentation that states specifically where the staff comes from, given the materials, it’s likely from somewhere in the Amazonian region of Brazil.

Based on folklore, anthropological studies, and research conducted by various museums we know that feathers have the ability to tell a lot about an object. Their mere use may indicate an affiliation to a particular tribe. Some tribes preferred feathers of one color while other preferred feathers of another color. Objects that included larger feathers were likely objects used by the males of the tribe while females would use or wear objects with smaller feathers.

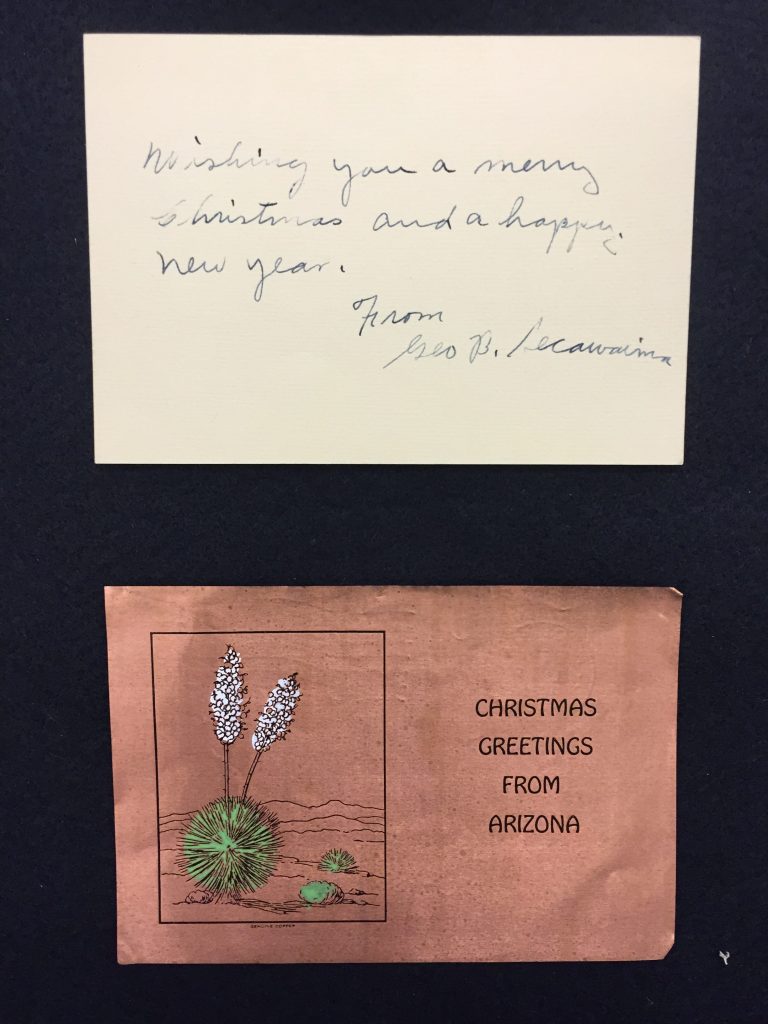

Hopi bowl, Object ID 2003.5.41, Melville Collection

Place of origin: Polacca, Arizona

Objects within the Melville collection are significant for a few reasons. The collection is supplemented by archival documentation. This is often rare when looking through 19th and 20th century collections. At that time, the contextual information surrounding the object – where it was found or purchased, who made it, what other objects it might be related to – was less important than the actual object itself. A lack in contextual information can make understanding the object difficult. Luckily, the Melville collection, comes with lots of contextual information!

In 1927 Carey E. and Maud Melville and their three children set out from Worcester, MA, to see the country in their new Ford Model T. Their trip included a three-week stay on Hopi lands in northeastern Arizona. There, through missionary friends at the First Mesa Baptist Church in Polacca, they became acquainted with local Hopi and Tewa artists. They collected, not as professional art dealers or ethnographers, but as tourists. However, they didn’t mindlessly acquire objects as souvenirs; the Melvilles were clearly interested in the objects’ perceived function and aesthetic, in who made them (and how), and in the experiences to be had and the relationships created via their acquisition.

This particular bowl is an example of Hopi-produced Polished Red Ware. The red surface is typically highly polished and sometimes slipped red. Polished red ware vessels will also typically include black pigment designs as well as, occasionally, white designs. Object 2003.5.41 is signed on its base by the maker, Ruth Takala.

Bone toothbrush, Object ID B21

Bone toothbrush, Object ID B21

Place of origin: Middletown, Connecticut

Wesleyan professors and students excavated in the Main Street Historic District in Middletown during the 1970s and 80s. Like most historic archaeology collections, this assemblage consists of glass, ceramics, building materials, and personal items. The local area of Middletown, particularly Main Street and its adjacent area, were a thriving and bustling port-city community during the 18th and 19th centuries. Main Street buildings housed either significant businesses or families with connections to significant and prosperous local businesses.

This is one of our favorite items to show and have people guess what it is. Many people guess that it is some kind of game. Despite its ability to stump people, bone toothbrushes are pretty common on historical archaeology sites. The bone used to form the actual handle and head of the toothbrush typically came from cow femurs. The bristles came from some type of coarse animal hair, such as boar, horse, or badger. The coarseness of the animal hair bristles actually often did more harm than good as the hair was prone to puncture the brusher’s gums, leading to infection. Hopefully this makes you thankful for the modern advances in toothbrush design as you brush your teeth later today!

Posted by Sarah Hoynes ’16