While cleaning out my room over the summer, I found a box containing my old collection of Wheat Pennies. Minted between 1909 and 1956, Wheat Pennies represent US coin collecting at its most basic level. The obverse of a Wheat Penny is identical to that of a penny minted in 2017, while the reverse bears the phrase “One Cent, United States of America” in the center, flanked by two stalks of wheat along the edges. Many Wheat Pennies are still in circulation, so the task of collecting them often comes down to inspecting any pennies received as change at the grocery store.

At around the same time I was rediscovering my collection of old coins, Wesleyan University Archaeology and Anthropology Collections (and follow us here!) was making a similar discovery: an enormous numismatic collection tucked away in the back of the Earth and Environmental Science storeroom. (See this News @ Wesleyan story for more information on the project which yielded this coin discovery!) Most of the coins in this collection did not originate in the United States, and those that did are well over 100 years old, and would be unlikely to surface in a cash register in 2017; thousands of coins, spanning at least three continents and at least 1000 years, waiting patiently for someone to do some spring-cleaning.

Although the collection was housed in the E&ES storeroom, the coins do belong to the Archaeology Collections. We know this for several reasons: First of all, as a general rule, numismatics falls under the purview of archaeology and anthropology, not earth and environmental science. Secondly, previous collections managers have attempted to integrate the coins into the modern archival system and, consequently, a small portion of the collection already lives in our storeroom. Lastly, many of the coins possess accession numbers that correspond to the Archaeology Collections’ earliest method of cataloging artifacts dating back to the Orange Judd Museum of Natural History, which opened in 1871 and closed in 1957. One of our ongoing projects for all of our collections is the assignment of trinomial catalog numbers to all of our artifacts, but for a long time, Wesleyan’s museum simply gave items a number as they arrived. A separate catalog was created for numismatics, but these designations were also simply numerical, beginning with 1 and ending somewhere after 3000. Many of the coins I have catalogued thus far appear to have been some of the earliest numismatics acceded into the collection; I have encountered coins with accession numbers as low as 36!

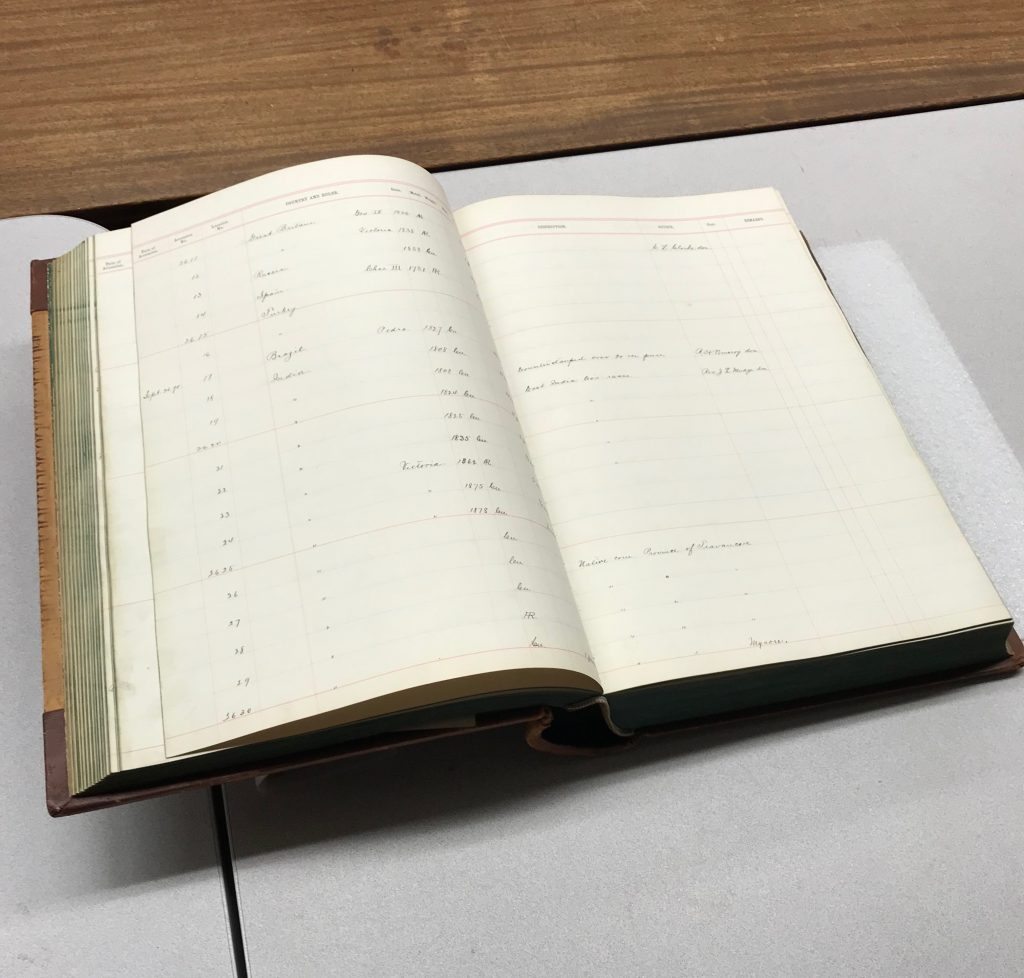

The only complete record of these numbers lives in an accession book so old that it could belong in a museum itself. In fact, Archaeology Collections had to receive permission from Special Collections in order to keep the book in our storeroom, rather than in the archive in Olin. The entries in this book are handwritten, often in hasty scrawl that requires a bit of imagination to decipher. The descriptions are limited, but they are generally enough to confirm that the number written directly on a coin matches the corresponding entry in the book.

This brings us to the task at hand. One by one, each of these coins must be examined, entered into a spreadsheet, and given a place in our collection, where it belongs. I cannot stress the “one-by-one” aspect of this project enough because, again, this collection comprises THOUSANDS of coins. To put that amount into perspective, in over a month I have catalogued fewer than 250 entries. There are thousands of coins now, and when I graduate in the spring, there will still probably be thousands of coins left. Like so many of the projects I have encountered as a student worker in Wesleyan’s Archaeology Collections, including Steven Dyson’s old records and the NAGPRA process, I won’t see the end of this endeavor.

I’ve learned that working on a long and drawn-out project takes patience, but working on a project I know I will leave unfinished takes a different kind of endurance. As a whole, the process has a specific end-goal, but my part of it doesn’t. It’s not depressing, exactly, but it’s not invigorating either. Setting smaller goals helps. A new cabinet was purchased for the numismatic collection—we will likely need at least one more to fit them all—and I am very slowly filling up the very first drawer in this first cabinet. Coin by coin, row by row. I’m hoping to finish that first drawer by winter break, and then next semester, I’ll start the second drawer. I think I’ll fill that one was well, but maybe I won’t. Someone will, though.

Thinking about the handwriting in the old accession book helps, too. I have encountered at least three distinct scripts in that book, which means at least three different people had a hand in maintaining the collection, holding a dialogue over time in the pages of the catalog. My handwriting isn’t in the book, but it’s on the labels I write out for each of the coins before I place them in their new case. It makes me feel like I’ve joined that dialogue because from now on, whenever someone wants to learn about those coins, they’ll start with the labels I’ve written and they’ll end with the entries in the accession book. It’s a process, of which I am now a part, and that won’t change when I graduate. And who knows? Maybe one day, I’ll visit for a reunion to find that whole case filled, top to bottom. And maybe there will be students working on a new project, with no end in sight.

By: Sophia Shoulson, ’18