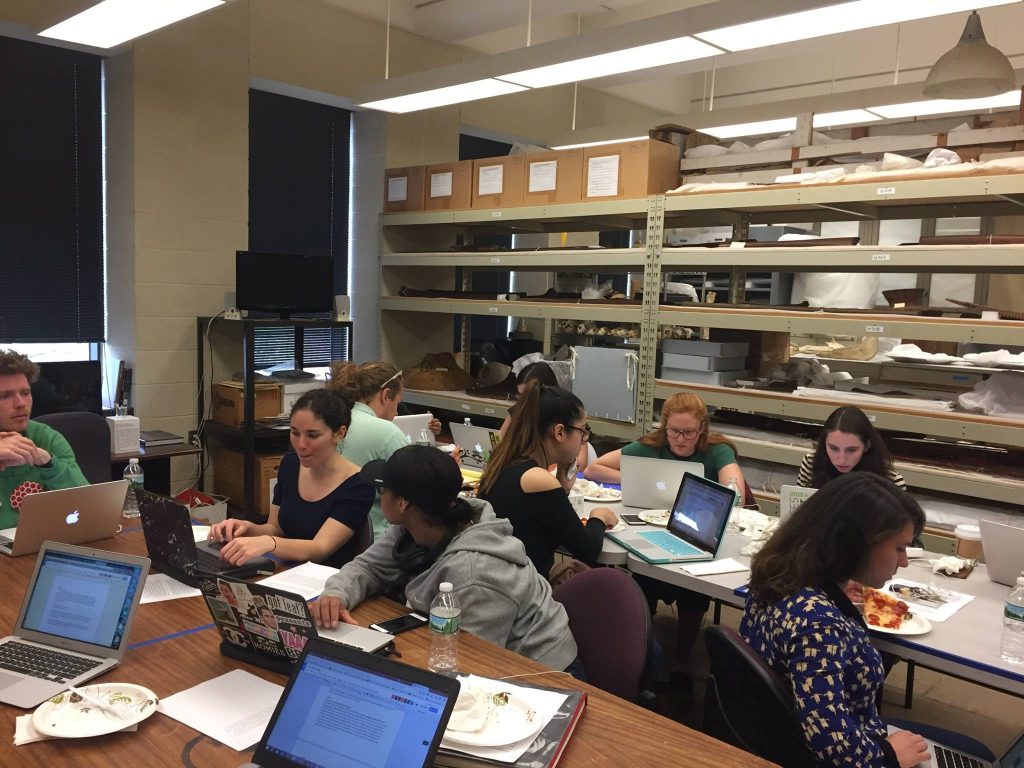

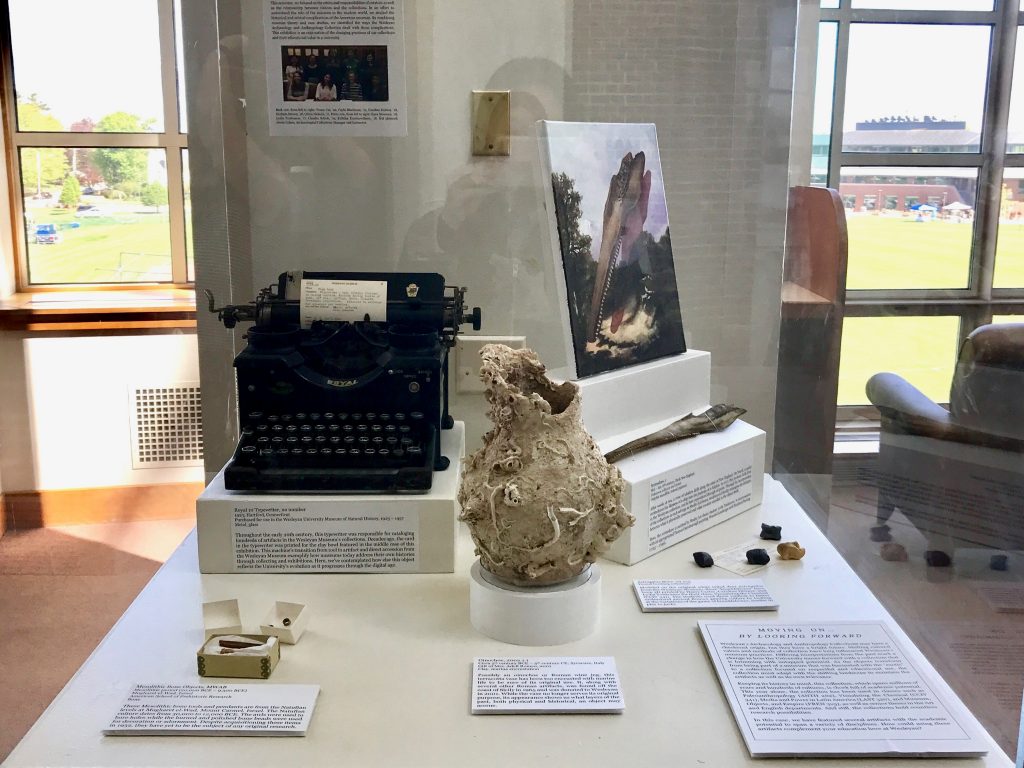

For the first time in recent history, the Archaeology Program is offering interested students the opportunity to work on hands-on research projects and lab work within the Archaeology and Anthropology Collections. With the 35,000 in the collection, one can only imagine the wealth of original research topics! In this blog post, hear from three students who are currently conducting work on their research projects. Find out what they’ve learned so far and what directions they plan to take in their ongoing projects.

Itai Klaidman-Rinat, class of 2021

The research that I have been conducting for Wesleyan’s Archaeology Collections revolves around an individual named Karl Pomeroy Harrington. Harrington was a Wesleyan alum and later taught here as a professor of classics. His vehement interest in Roman history coupled with his expansive travels led to his acquisition of a significant number of ancient Roman artifacts many of which have found their way into Wesleyan’s collection.

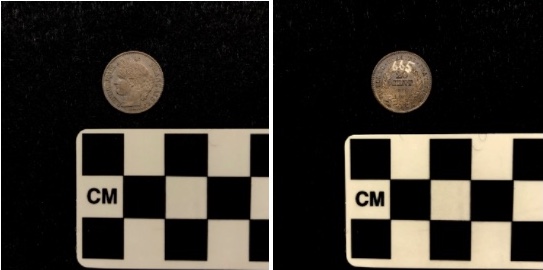

The artifacts include figurine heads, shards of mosaics, architectural debris, oil lamps, vases and a collection of coins numbered in the thousands. My research aims to provide context for the Harrington collection in a number of ways. First, what are the origins of the artifacts themselves? Where do they originate chronologically and geographically within the Roman Empire? Secondly, how were the various items acquired by Harrington, and in turn end up in the collection here at Wesleyan? Luckily, Harrington himself provides clues pertaining to both questions within his autobiography; Karl Pomeroy Harrington: The Autobiography of a Vigorous and Versatile Professor.

Following Harrington’s graduation from Wesleyan in 1882, he spent a number of years furthering his education. He taught at Westfield and Wilbraham before studying in Europe at the University of Berlin. He spent two years in Europe from 1887-1889 in which he not only studied in Berlin, but also traveled to Greece and Italy. Although there is little evidence that Harrington actually acquired any artifacts during these two years (however it is possible), it certainly exposed him to the world of archaeology and wet his appetite for exploring Roman antiquity in person. He describes his growing interest in archaeology, “I continued my archaeological studies in the great museum there (Naples) and at Pompeii, Herculaneum, the ruins at Baiae, ancient Cumae, and the temples of Paestrum” (Harrington 82).

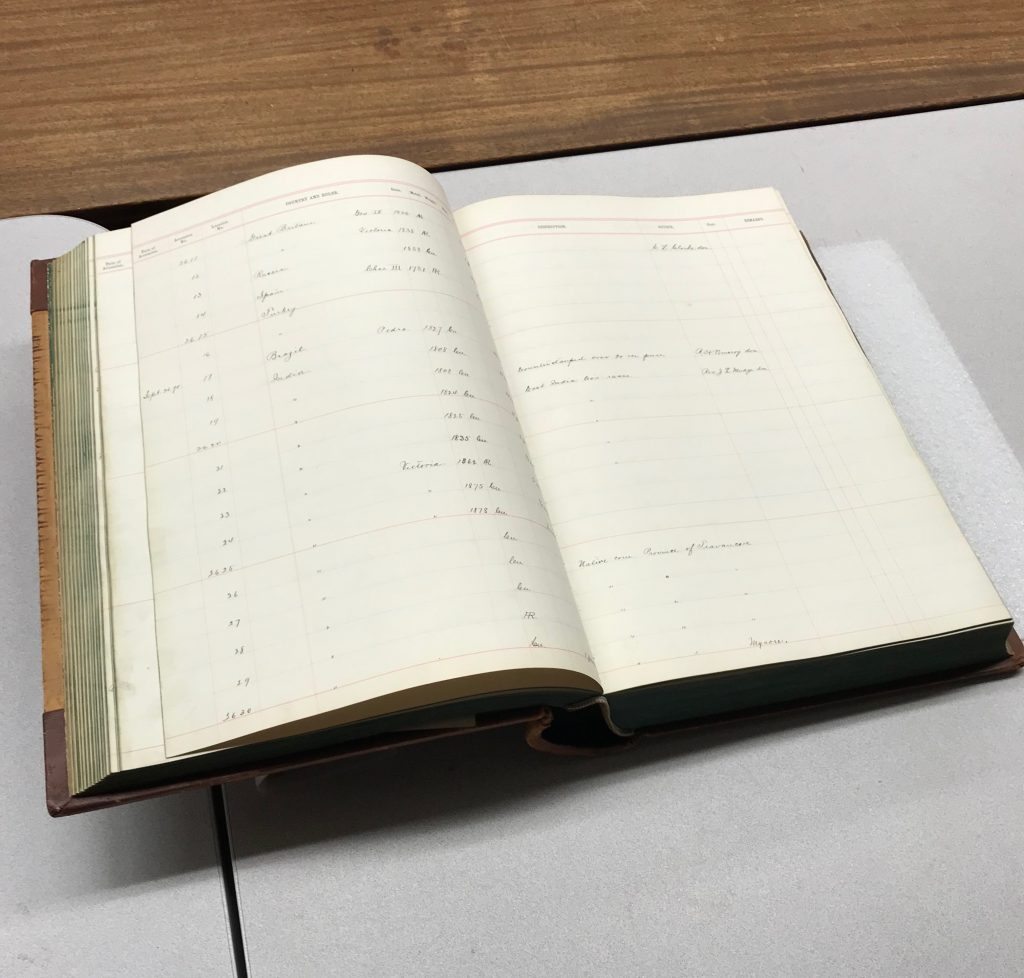

Following his two year stint in Europe, Harrington was a Latin tutor at Wesleyan for two years before a year of graduate school at Yale. Afterwards, he taught Latin at the University of North Carolina, and University of Maine before being hired by Wesleyan in 1905. In 1912 he had his first sabbatical year, which clearly yielded many of the artifacts in Wesleyan’s collection today. He traveled with his family and they were based in Rome. He made connections with the American School in Rome and was thus allowed to accompany Professor Van Buren on many archaeological excursions. Over the course of the year, Harrington traveled throughout Italy’s mainland as well as Sicily and Roman Africa. Often he literally describes finding artifacts that are in the collection, such as when Etruscan tombs in Cerveteri “yielded a number of pottery fragments” (Harrington, 184). However, it isn’t always so simple to figure out where he came into possession of certain relics, for some of which the origins will remain a mystery. For example, there is no mention of the coins throughout the book which is hard to believe considering the magnitude of the collection.

It is important to note that the coin collection is actually called “The Calvin Sears Harrington Coin Collection,” which is the name of Karl’s father who also was a professor of classics at Wesleyan. The coins were donated by Karl, but they may very well have been collected by his father who is known to have also traveled in Europe during his lifetime. Harrington also traveled around the world, beginning in the San Francisco Bay (where his daughter and her husband, who taught at UC Berkeley, lived), traveling through Asia and Europe before ultimately returning to Middletown. During that trip he continued to obtain valuable historic artifacts and explore the wonders of the world.

Harrington, having been exceedingly knowledgeable about Roman history, often muses in his writing about what occurred in the places to which he traveled. However, he writes with a vagueness that suggests he assumes the reader possesses the same knowledge that he does. The ultimate goal of this research project is to write an academic paper in which I provide context for the Harrington collection by describing his travels and acquisition of artifacts including a detailed map of everywhere he went and specifically marking places where he obtained objects. I also intend to research the historical events and figures from Roman history that he mentions in relation to the places that he travels to in order to enrich the narrative between the present, Harrington’s time, and Ancient Rome.

Harrington, Eliza C. Chase. Memories of the Life of Calvin Sears Harrington, D.d. General Books, 2012.

Potter, Mabel Harrington. Karl Pomeroy Harrington: the Autobiography of a Versatile and Vigorous Professor. Publisher Not Identified, 1975.

Constantinos Koufis, Art Studio and Archaeology major, class of 2019

My internship in Wesleyan’s Archaeology and Anthropology collections began with cataloging ceramics and glass–mostly pearleware shards. Excavated from Middletown’s Main Street from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, the objects are recorded only in the field notebooks from the original dig. Most of the objects that I have entered into the digital table that I am creating are in bags with labels. The labels vary in specificity; the most specific labels have a number preceded by the letter “S” (eg. S24). The less specific bags only have sector coordinates (eg. So 1 SW II). Some bags don’t have labels at all; in those cases I am only able to enter into the table what I observe myself. So far I have cataloged five boxes of objects excavated from the Southmayd family house site, once located on the southeast corner of Main Street and Martin Luther King, Jr Ave, north of the Inn at Middletown. The original house was moved across the street with several other historically significant houses. Because of the monotonous nature of cataloging items, I have also been doing research into a completely different subject.

There are an abundance of woven artifacts in the collections but there is no space for them to be displayed. Likewise, there are not many items on display on the Wesleyan Archaeology and Anthropology highlights website. My plan for the next half of the semester is to compile a selection of different woven items from around the world and to create a page for them in the highlights section of the collections’ website. Right now, the highlights are of highly specific groups; what I am researching covers a broad range of times and cultures and presents an opportunity to give some items more exposure than they would normally have.

Carson Horky, History major, class of 2020

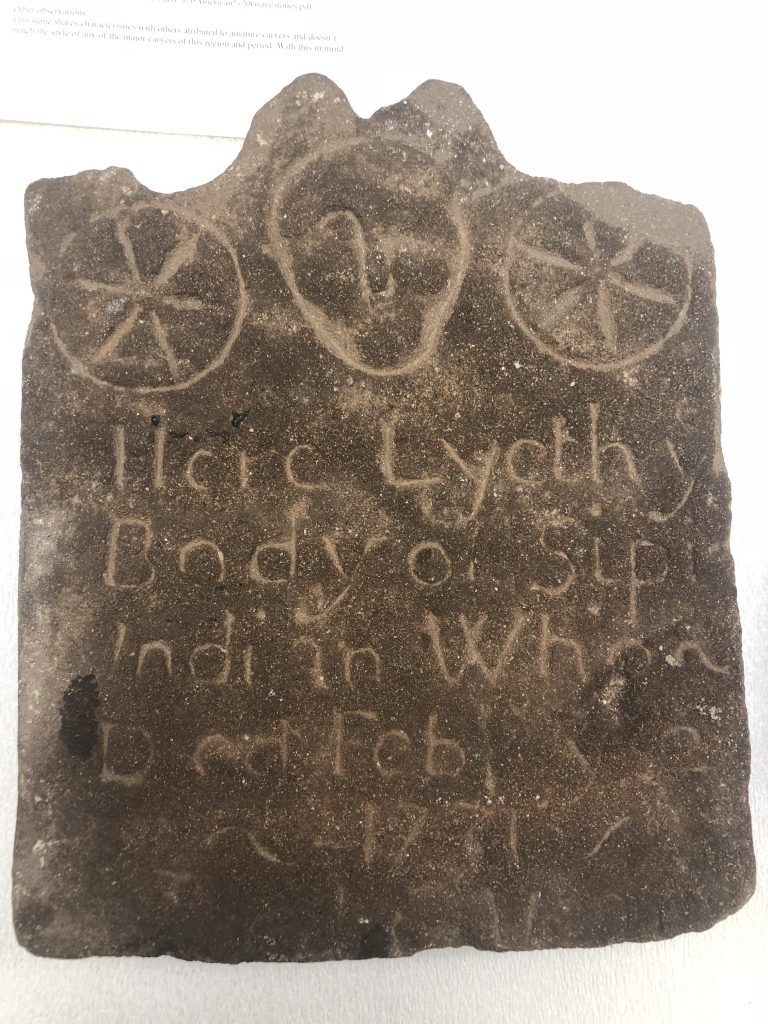

One of the Wesleyan University Archaeology and Anthropology Collection’s most unique objects is a gravestone that at first glance may look like a relatively common example of a Puritan stone. However, the inscription tells a different, more enigmatic story. It reads, “Here Lyeth [?] Body of Sipi Indian Who[?] Died Feb [?] 1731 Aged 6 Years.” There are almost no other contemporary examples from New England of Native American gravestone burials. If this stone does prove to be an example of a Native gravestone burial, it could have important implications for our understanding of Native death culture. Additionally, it may make this object a candidate for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

The history of the stone at Wesleyan is also a mystery, having been brought to the Wesleyan Museum in Judd Hall in 1872. Other than its date of arrival, we know practically nothing about its origins. After the museum closed in 1957, the stone was moved to an office on campus and it eventually made its way to the collections. The Middlesex County Historical Society also has no record of the stone or any individual named Sipi.

The stone itself is made from sandstone which may have been quarried in the Portland area (located just across the Connecticut River from Middletown). Assuming that the date of death on the stone is an accurate indicator of when it was made, we can approximately date it to 1731. Though definitely weathered, most of the inscription is readable and the symbols at the top of the stone are relatively clear.

The top of the stone features a human face flanked by two six-pointed rosettes. The face has a blank expression, long nose, small mouth, and puffy cheeks. We originally thought that it could be an example of a “death’s head,” a common image on Puritan graves. Most of the contemporary stones found in Haddam cemeteries feature death’s heads, so matching them with the Sipi stone would have been a potentially fruitful find. However, whereas death’s heads almost always have serrated teeth and wings, the plainness of the face on the Sipi stone seems to disqualify it from being a death’s head.

Alternatively, the face on the stone seems to look more like a “soul effigy,” found on some contemporary stones in the Portland area. Soul effigies, when paired with six-pointed rosettes, are often found on the gravestones of children, indicating that such a symbol would be a good match to the Sipi stone, as its inscription says that the person was six years old when they died. However, Puritan children were usually buried with or close to their parents. The Sipi stone, however, does not have any indication of parental presence. This is yet another example of the stone’s uniqueness.

Another aspect of the stone that makes it difficult to study is that it was likely carved by an amateur. The symbols at the top of the stone are not well-defined or precisely carved. For example, the inner lines of the rosettes are not uniform in size or depth of impression, something not typical of more traditional stones. Additionally, standard examples of Puritan stones feature lettering that looks rather exact—text that resembles something similar to the level of accuracy expected from modern laser inscription. The lettering on the Sipi stone, alternatively, is off-center and not uniformly sized. These features indicate that the stone was likely not done by a professional carver. With more typical examples of Puritan gravestones, specific styles and aesthetics can often be traced to individual carvers. This avenue of research is not particularly relevant to this stone, though it may be a compelling way to determine artistic influence.

One of the main questions that must be answered in order to better understand the significance of the stone is that of its original location. Professor Katherine Hermes and Alexandra Maravel from Central Connecticut State University already did some groundwork on attempting to determine the stone’s origin. They looked through records and cemeteries from Middletown and some surrounding areas, but unfortunately did not find anything relevant to the stone.

Based on word of mouth from Wesleyan faculty familiar with the stone, we have some reason to believe that it may have originally come from the confluence of the Connecticut and Salmon rivers. From this, we have focused most of our work on the Haddam area. Having surveyed the Thirty Mile Plantation and Higganum cemeteries, we have been unable to identify any similar contemporary stones. We are now looking into a place called “Graveyard Point” on the bank of the Salmon River, near its confluence with the Connecticut River. Graveyard Point no longer has any graves, but the name itself makes it seem promising as an original location for the stone.

As the semester continues, we will continue to look into Graveyard Point, specifically going through archives in Haddam to try to find out more about the history of the site. We also hope to look into more records, including death records, church records, and family plot records. We also would like to learn about possible Native etymologies of “Sipi,” as well as the history and archaeology of the Wangunk Meadow area. We are additionally doing some work with the political and cultural contexts of the Wangunk people, seeing as the Early Reservation period ended in 1732, meaning that the individual buried with the stone probably lived within a period of cultural transition.

Dethlefsen, Edwin, and James Deetz. “Death’s Heads, Cherubs, and Willow Trees: Experimental Archaeology in Colonial Cemeteries,” American Antiquity 31, no. 4 (1966).

Grant-Costa, Paul. “Wangunk,” Yale Indian Papers Project. Yale University. https://yipp.yale.edu/tribe/83.

Ludwig, Allen I., Graven Images: New England Stonecarving and Its Symbols, 1650-1815. Hanover: University Press of New England (1999).